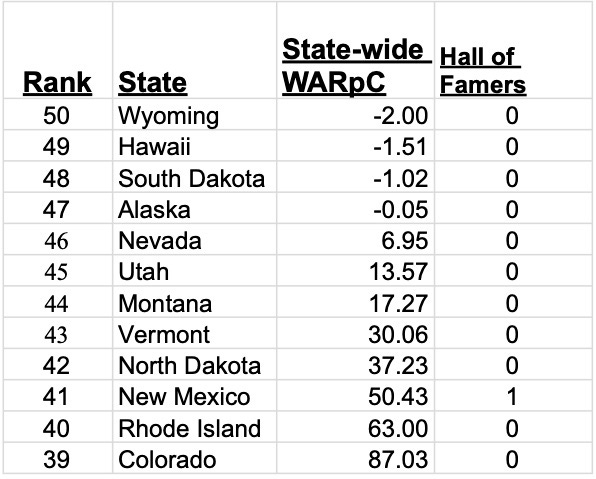

We’re counting down (or up, if you’re so inclined) to the state with the most buried baseball players, sorted by WAR. Ultimately we’ll reach the one cemetery with more valuable dead baseball players than any other!

Very exciting. Very Halloween season. For methodology and details, see the Introduction here.

We’ve left the stragglers (Wyoming, South Dakota, and Alaska) in Vol. 1, and said Aloha to the intriguing Hawaii in Vol. 2.

On to the flyover states, by WARpC (WAR per Cemetery) standards. Once again, thank you Baseball Reference for the sorting options and the numbers. So many numbers.

First state up is Nevada. Bo Belinsky (.5 WAR, Davis Memorial Park, Las Vegas) tossed the first-ever MLB no-hitter on the west coast in 1962. It was just his fourth career start. He went on to post a 4.10 ERA along a flashy, but erratic, eight-year career. He lived an equally chaotic life. He died of a heart attack at 64 in Las Vegas. He was famously a ladies man, enough so to warrant a tell-all biography by Maury Allen, Bo: Pitching and Wooing; an extended role in his ex-wife Mamie Van Doren’s autobiography, Playing the Field; and a mention in The Baseball Project song THEY PLAYED BASEBALL.

In the same cemetery, fans of the 1950s New York Giants can also visit James “Dusty” Rhodes (3.7 WAR). His 1954 World Series heroics vs. Cleveland are legendary. In Game One, with the game tied 2-2 in the 10th inning (a tie preserved by Willie Mays’ THE CATCH earlier in the game), Rhodes pinch-hit a wind-aided three-run walk-off homer. In game two, Rhodes went 2 for 2 with a pinch-hit RBI single and a solo home run. The Giants won 3-1. In game three, Rhodes was called on to pinch hit again, singling in two runs in a 6-2 Giants win. Rhodes’ four consecutive hits and seven RBIs lead to a swep, a Giants World Championship, and Rhodes never needing to buy a drink in New York City again. When asked if he was upset that he didn’t play in the game four clincher, “It was just as well. After the third game I was drinking to everybody’s health so much that I just about ruined mine.” His manager Leo Durocher affectionately called him a buffoon, “I love having him on my ball clube because of his personality and the funny things he did that kept everybody loose. But I couldn’t have stood two of him.”

One graveyard, two nice grave markers from two vividly different personalities.

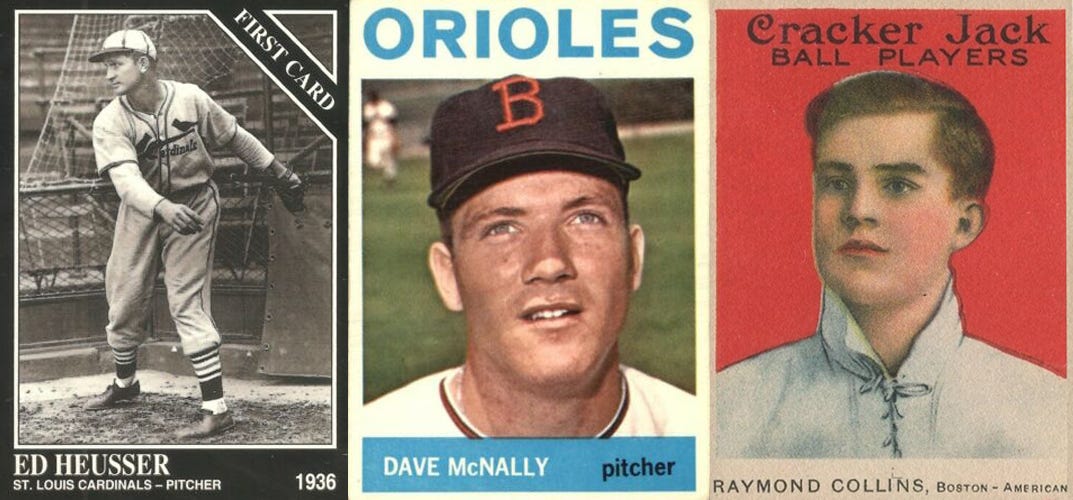

Ten of Utah’s thirteen statewide WARpC belongs to Ed Heusser (10.1 WAR, Bountiful Memorial Park, Bountiful). He pitched in nine seasons between 1935 and 1948, leading the league in 1944 with an ERA of 2.38. His nickname “The Wild Elk of The Wasatch” is, unfortunately, not on his headstone. If you’ve ventured out to Bountiful (just north of Salt Lake City), you should also stop by the tombstone of Keene Curtis, character actor with a hundred credits, but best known as John Allen Hill, the asshole who owns of the bar above Cheers (notable Baseball TV show).

Three-time All-Star pitcher Dave McNally’s WAR (25.5 WAR to be exact, Yellowstone Valley Memorial Park, Billings) far exceeds the Montana state-wide total, since ten of the fourteen players buried there are in negative territory. McNally was an ace on the 1960s Orioles and was the third inductee into the Orioles Hall of Fame after Brooks and Frank Robinson. McNally and Andy Messersmith were part of the landmark 1975 court case that ended baseball’s reserve clause and created free agency. In this respect, every player that’s made it to free agency should make a Billings pilgrimage and a McNally graveside toast.

Lefty pitcher Ray Collins (25.6 WAR, Village Cemetery, Colchester), is by-far the highlight of Vermont’s fourteen buried players. In seven seasons (1909-1915) with the Red Sox, he had a 2.53 ERA and helped them win a World Series in 1912. On September 14, 1914, he pitched two complete game wins in a double header. A maple syrup farmer in his post-baseball career, the state of Vermont placed a historical marker at his family farm in 1998.

North Dakota can claim Roger Maris (38.2 WAR, Holy Cross Cemetery, Fargo) as their WARpc herald, but little else; the other four buried players combine for -.9 WAR. The Maris headstone has the numbers 61 and ’61 flanking an engraved ballplayer swinging a bat. If you’re not sure what those numbers are referencing, WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN? Maris shares his final resting place with Ken Hunt (-.07 WAR), a childhood friend to Maris and his roommate with the 1960 Yankees. Hunt was a promising all-around athlete, but shoulder injuries curtailed his career, apart from a respectable 1961 season with the expansion California Angels. The next year Hunt met and married Patty Lilley, mother to Patrick Lilley, AKA child actor Butch Patrick, AKA Eddie Munster! Hunt and Leo Durocher appeared in an episode of the Munsters, “Herman the Rookie.”

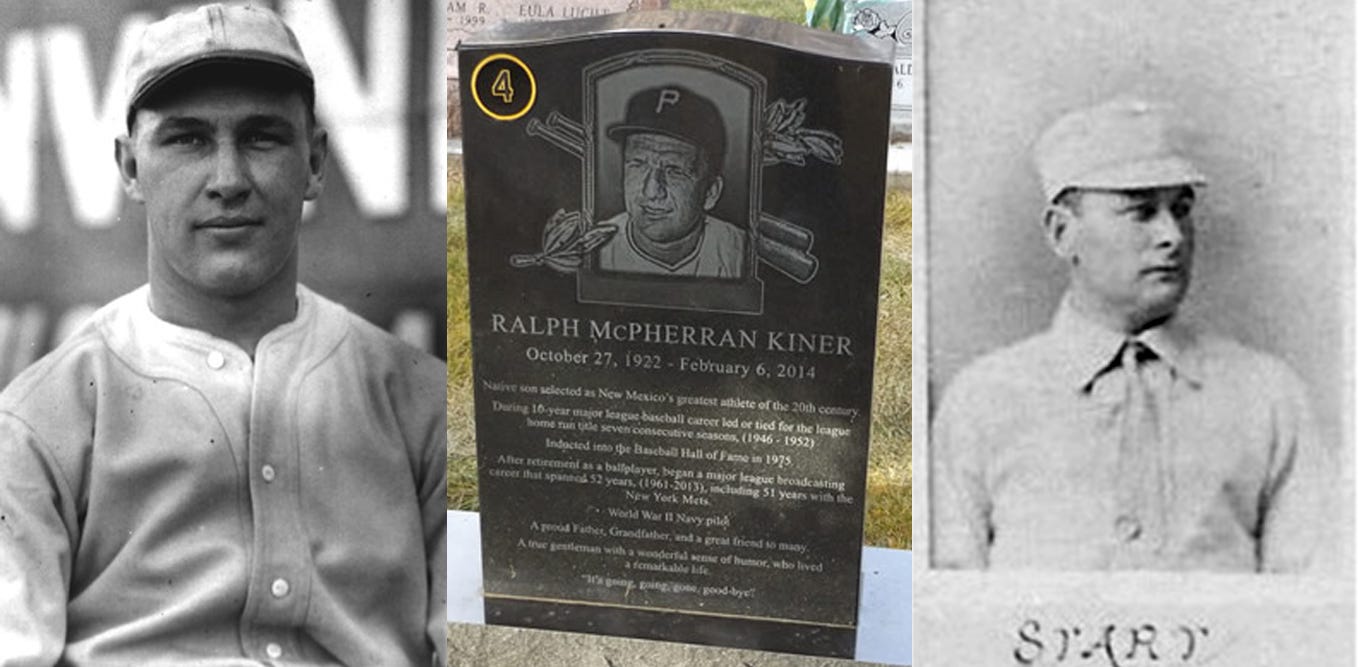

New Mexico boasts the gravesite of Hall of Famer Ralph Kiner (48.1 WAR, Greenlawn Cemetery, Farmington). In his stellar playing career, he led (or tied) the league in home runs seven consecutive seasons with the Pirates (1946-1952). As a long-time Mets broadcaster, he is oft-remembered for his signature home run call, “It is going, going, gone. Goodbye!” which is inscribed on his tombstone.

Moving away from the square-ish states in Mountain Time, Rhode Island possesses fifty buried ex-major leaguers. Kind of impressive. Joe “Old Reliable” Start (32.5 WAR, Riverside Cemetery, Pawtucket) is your best bet though. Over his sixteen seasons of official Major League baseball (1871-1886), Start hit to the tune of a 121 OPS+, mostly for the Providence Grays. He actually played as early as 1859, adapting to the changes of baseball from amatuer playground game to professional league.

Just ten minutes down the road is Harold Charles Neubauer (-.4 WAR, Swan Point Cemetery, Providence). Visit him not for his career total of 10 innings pitched in 1925, nor his 12.19 ERA, but for his nickname, “Handsome Hal, The Hoboken Hercules.” Swan Point is quite the historical cemetery, but for our interests, I’ll throw out these celebs: All-American Girls pitcher Louis “Lou” Arnold, who played four seasons for the South Bend (Indiana) Blue Sox, and author H.P. Lovecraft.

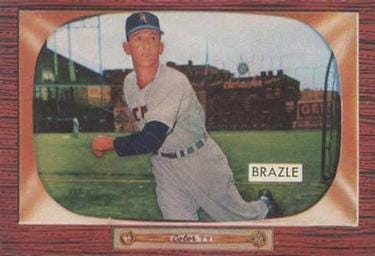

When in Colorado, go skiing or rafting or craft beer drinking, since the dead player cemetery tourism is pretty lean. If you’re exploring the national parks of south-west Colorado, you’re close to the WAR headliner of the Centennial State, Alpha “Cotton” Brazle (20.1 WAR, Fairview Cemetery, Yellow Jacket). A minor league journeyman until age 29, Brazle caught on in the majors only after two years of WWII service. The rubber-arm lefty, a side-winding sinker-baller, then pitched eight years for the Cardinals, amassing 442 appearances and a 3.31 career ERA. He lead the National League in saves (before that was even a stat) in 1952 and 1953. Maybe baseball’s first proto-closer.

Do I have a pithy theme to encapsulate this mishmash of drunks, heroes, also-rans, buffoons, common cards, innovators, and All-Stars? I do. Of course, I do.

These guys, these baseball guys, entertained people with their skills for a minute, or a year, or a decade. They continue to entertain from beyond the grave, in so, so many different ways.

Stepfather of Eddie Munster! Historical marker in Vermont! Dusty Rhodes, not the wrestler! Players who challenged baseball’s near-100-year indentured servitude contracts! The Hoboken Hercules!

To say that baseball had a diversity problem is to completely misrepresent the systematic racism that kept The American and National League segregated for 50 years. These guys, these baseball guys, could not have been more different from each other. Yet there was still something not really that different. How many more incredible players, incredible people, we would have gotten to know, if that racism was not institutionalized? Those baseball guys are out there, too. We’ll just have to dig a little deeper to find ‘em. And dig we shall.*

(*Not literally.)

Nice! This piece is also WAR: Writing Above Reproach.

I suspect there was more to Maris and Hunt’s “friendship” to be buried next to each other!