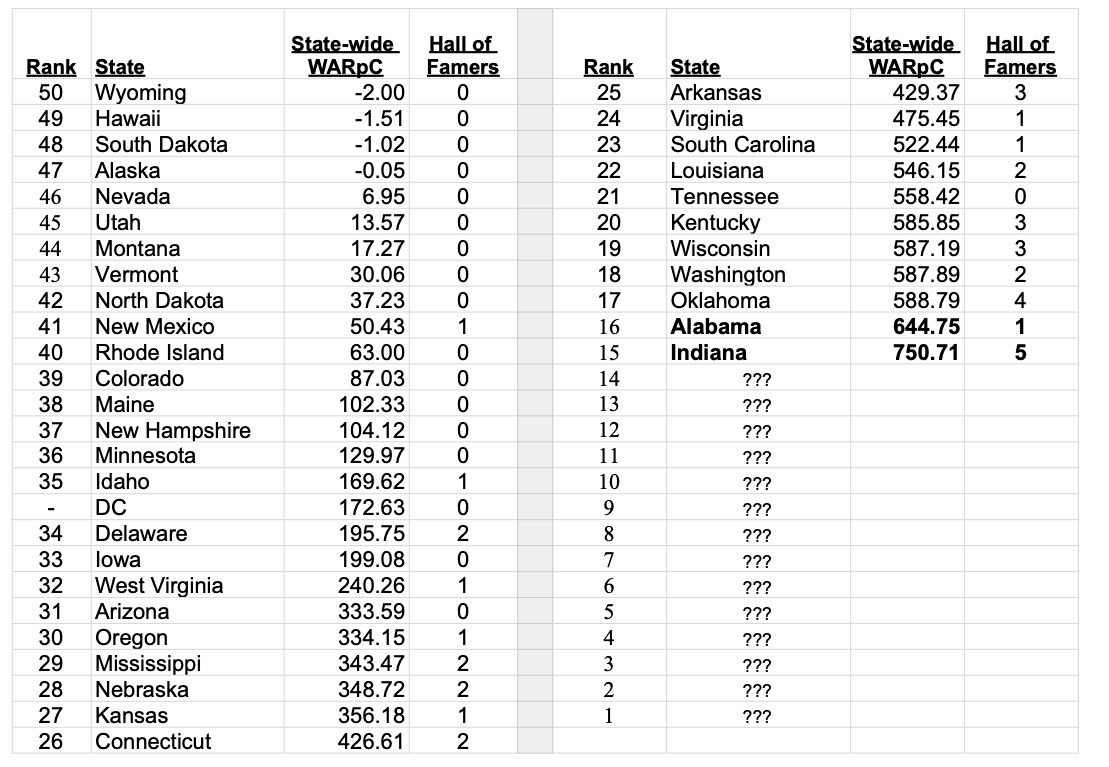

Hello to long-time readers and recent subscribers! Thank you for tuning in. Here’s Volume 9 of Cemetery WAR, where I post my research on baseball cemeteries, sorted by the cumulative career WAR of the players buried therein. Effectively Wild, a Fangraphs Podcast, and the NINE Conference were kind enough to have me talk about this project recently.

For research methodology, here’s Vol. 1. For a catch-up on previously covered states, here’s Vol. 8.

Today we’ll sort out the Alabama Dixies, find a Yankee killer, and road-trip through baseball-rich(??) Indiana!

Alabama is more known for its football history, but we’re going to completely ignore that. This is a baseball-only zone. We’re starting at Memorial Park in Tuscaloosa, the eternal home to just four players, but the cemetery with the 2nd most WARpC in Alabama.

Hall of Famer Joe Sewell (54.7 WAR) took over shortstop for Cleveland after Ray Chapman’s unfortunate death by hit-by-pitch in 1920 and stayed there for eleven years. After three more years with the Yankees, Sewell finished with 8,333 plate appearances, a .312 batting average, and just 114 strikeouts. The day of his MLB debut, he was handed a black 41-ounce bat. He named it “Black Betsy” and used that one bat his entire career. It’s on display at the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. Sewell coached the University of Alabama baseball team in the 1960s and their home, Sewell-Thomas Stadium, is nicknamed “The Joe.” One last juicy tidbit: Sewell was in the lineup when Babe Ruth supposedly called his shot in the 1932 World Series and is quoted, “I don’t care what anybody says, he did it.”

Other Tuscaloosa Memorial Park residents: Riggs “Old Hoss” Stephenson (32.8 WAR) played fourteen seasons with the Indians and Cubs in the 1920 and 1930s, with a .336 lifetime batting average, twenty-second best all-time. Detroit pitcher Frank “Yankee Killer” Lary (30.3 WAR) was 28-13 against dominant Yankee teams of the 1950s & 1960s and has the old English D on this grave marker. Plus, that’s an 80–grade nickname for a southern cemetery. Ike Boone (6 WAR) had an 8-year career in the 1920s for a string of last-place Red Sox teams and gets a mention here solely out of proximity and the completionist in me.

To nearby Birmingham we go, where 53 major leaguers are interred. The biggest names are in Elmwood Cemetery, the #1 Alabama WARpC cemetery.

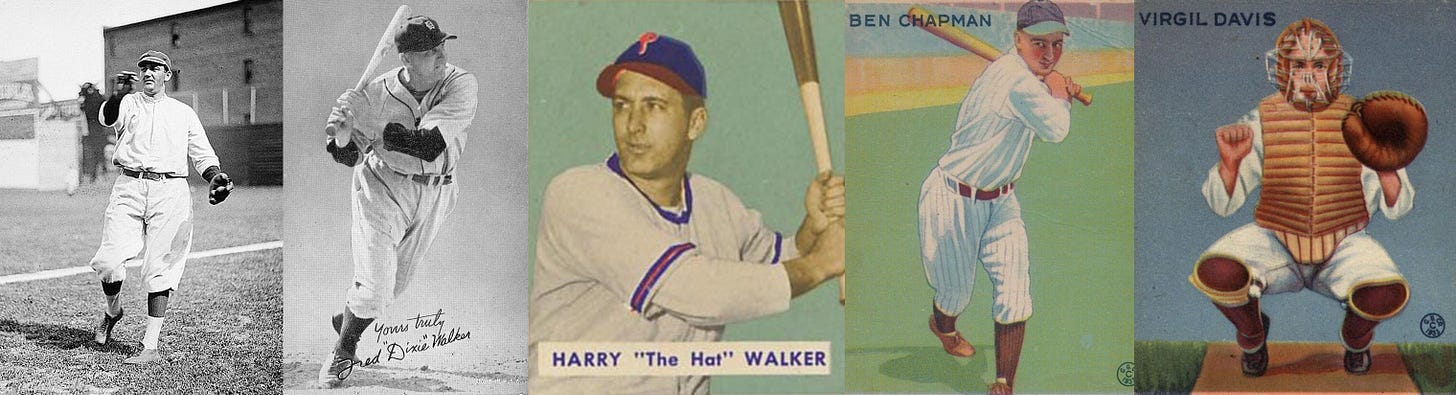

There are three “Dixie” Walkers buried in Alabama. Maybe that’s not all that surprising. We’ll try to straighten out any confusion though. Ewart “Dixie” Walker (2.9 WAR, Elmwood Cemetery, Birmingham) pitched from 1909-1912 for the Washington Senators. His brother Ernie (.2 WAR, Fraternal Cemetery, Birmingham) played 3 years in the majors for the St. Louis Browns. It’s unsurprising that Ewart’s two sons made the majors.

The younger brother Harry “Little Dixie” Walker (12.4 WAR, Cedar Grove Cemetery, Leeds) earned his other nickname “Harry The Hat” from his fidgeting and cap adjusting in the batter’s box. He was a singles-slapping center fielder for every bad NL team of the 1940s, managed the Pirates & Astros in the 1960s, and started the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s baseball program in 1978.

Older brother Fred “Dixie” Walker (45.1 WAR, Elwood Cemetery, Birmingham) played 18 years for the Yankees & White Sox and was a four-time All-Star for the Brooklyn Dodgers. This “Dixie” deserved his nickname as he was among the players who protested Jackie Robinson’s promotion to the Dodgers in the spring of 1947 and asked to be traded because of it. After 20 years managing minor league teams and scouting for other organizations, Fred Walker returned to the Dodgers as a batting coach from 1969-1976. He was praised by many black players for his help, including Dusty Baker, Jim Wynn, and Maury Wills. After Robinson’s death, Fred Walker said, “I’m as sad as I could possibly be… Me being a Southern boy and raised in the South, it wasn’t easy for me to accept Jackie when he came up. At the time I was resentful of Jack, and I made no bones about it. But he and I were shaking hands at the end.”

Both “Dixie” Fred and “Little Dixie” Harry won batting titles, the only brother duo in MLB history to do so. They started the 1947 All-Star game together.

Here’s a (probably unnecessary) chart of all “Dixies” to earn major league time.

Before we leave Birmingham, let’s visit two more players.

Ben Chapman (42.8 WAR, Elmwood Cemetery) garnered some quality nicknames after leading the American League in stolen bases from 1931-1933 - “Dixie Flyer” and “Alabama Flash” - but he doesn’t fare as well in the “I’m not a racist any more” category of Jackie Robinson detractors. Among numerous incidents through his career, these merit mention: in 1934, an estimated 15,000 New Yorkers signed a petition to have the Yankees release Chapman after anti-Semitic comments; Chapman chased a fan out of Yankee stadium after exchanging insults; and Chapman was suspended from baseball for a year after punching a minor league umpire in 1943. His reported Robinson comments are horrific, his defense that “bench jockeying [insulting opposing players to rattle them] has always been part of the game. Maybe I was rougher at it than some” is questionable at best.

Virgil “Spud” Davis (22.4 WAR, Elmwood Cemetery) caught 1,458 games and hit a career .308 (a 110 OPS+), bouncing from Philadelphia to St. Louis to Pittsburgh, from 1928 to 1945. In contrast to his cemetery-mates, Davis was mild-mannered. He didn’t fit in with the rough and tumble “Gas-House Gang” during his time with the Cardinals, being described as “the personification of the Southern Gentleman… he does not strut into hotel lobbies, on main thoroughfares, or on the ball field. The Spud does not poke his nose into open conversations, but is reserved and retiring. He does not horde [sic] his money, nor dress in the height of fashion, but enjoys good shows and is fond of movies.” Spud was no Rube.

Now you have an itinerary for your dead baseball player tour when visiting Birmingham for the Negros Leagues Tribute Game at Rickwood Field (June 18, 2024, Giants vs. Cardinals), the oldest professional ballpark in America.

Like Alabama and football, Indiana has a long and storied basketball history. Which we will also completely ignore. Indiana baseball impresses with its WARpC total, the second-most among states without a major league team, and its FIVE(!) buried hall of farmers. We’ll organize our dead player visitations as stopovers along an epic Indiana minor league baseball road-trip. Get comfortable as we travel from north (say, Chicago) to south (say, Louisville).

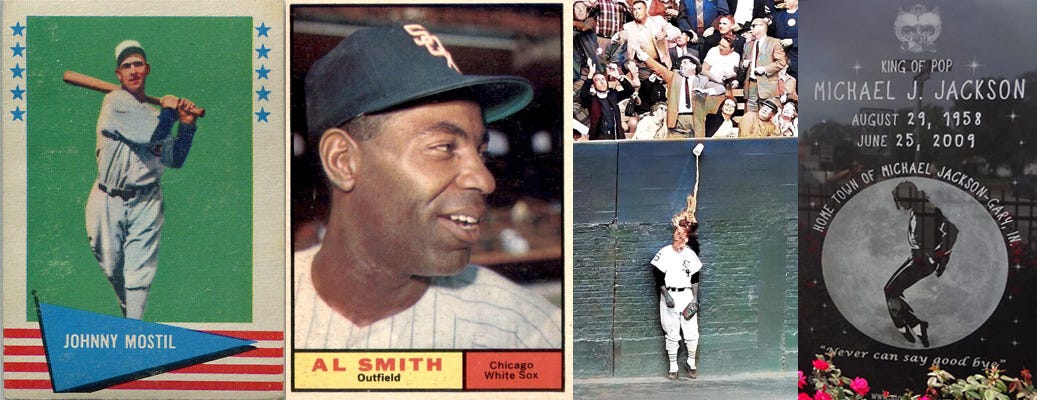

First stop: Gary! Indiana! Those exclamation points could be construed as sarcastic. Gary does feel like the New Jersey turnpike of the midwest. But we’re here to change that. For starters, we’re going to an American Association game (one of the MLB Partnership leagues) to see the Gary Southshore Railcats play at Steel Yard Stadium. While Gary may not be your typical vacation destination, does $3 Taco Tuesdays and $1 Pierogi Wednesdays change your mind? How about the birth home of the Jackson 5?

Still no? Gary also offers two deceased baseball players with crazy stories, well worth your time.

Johnny Mostil (24.4 WAR, Mount Mercy Cemetery, Gary) got a cup of coffee with the 1918 Chicago White Sox, was in the minors for the 1919 “Black Sox” scandal, then played 8 years for the subsequently gutted Southsiders. A speedy center fielder with a .300 career batting average, Mostil accrued the third-most WAR for the White Sox in the 1920s. In 1927, at age 31, with his health in decline from a neurological disorder, Mostil was found in a spring training hotel bathroom, in a pool of blood, with a dozen lacerations to his neck, legs, wrists, and chest from a pocket knife and razor. Initial news reports implied the wounds were self-imposed. Later speculation leaned toward a locker room affair gone wrong, but no teammate ever came forward with an accusation. Mostil recovered and returned to playing baseball, but was never the same. And never revealed what really happened. It’s an episode of HBO’s Perry Mason waiting to happen!

Al “Fuzzy” Smith (20.9 WAR, Oak Hill Cemetery, Gary) played in the Negro American League (Cleveland Buckeyes), integrated the Class A Eastern League in 1949, was the first black player for the Indianapolis Indians in 1952, and after a 15-year big league career has been called the “Forrest Gump” of baseball.

Smith was on the opposing team when Willie Mays made “The Catch” in the 1954 World series. Smith was traded from Cleveland to the White Sox for beloved Minnie Minoso. After the resulting fan reaction, White Sox owner Bill Veeck held “Al Smith Night”, where anyone named Smith (or similar) would get into the game for free, as long as they wore a button that said “I’m a Smith and I’m for Al.” Smith is credited with scoring from second base on a sacrifice fly four times, a record that still stands. When Veeck installed the first fireworks-exploding scoreboard in 1960, the first ever home run was hit by who else? Al Smith. Lastly, in Game 2 of the 1959 World Series, a fan in the front row of the outfield reached for a home run ball, knocking his beer perfectly onto the player standing below, Al Smith.

I hereby declare Al “Fuzzy” Smith the Patron Saint of Tinker Taylor Soler Spiezio for most numerous and most interesting factoids for a player few have ever heard of.

To quote Gary’s most famous sons and daughters…

Automatic, systematic (Ooh bop tiddley bop)

Full of color, self-contained (Ooh bop tiddley bop)

Tuned and channeled to your vibes (Ooh bop tiddley bop)

Captivating, stimulating (Ooh bop tiddley bop)

She’s such a sexy lady (Ooh bop tiddley bop)

Filled with space-age design (Ooh bop tiddley bop)

The Jackson 5 were certainly channeling their hometown while composing this disco classic, “Dancin’ Machine.” Thank you, Gary, Indiana, you rule.

For our second Indiana stop, we’ll drive one hour due east, for a South Bend Cubs game (High-A, Cubs). Every Tuesday is “Paws and Claws” night. Bring your dog to the ballpark and enjoy $4 cans of White Claw! It’s unclear whether the disclaimer “Dog owners must fill out a waiver prior to entry” pertains to the canines or the White Claws.

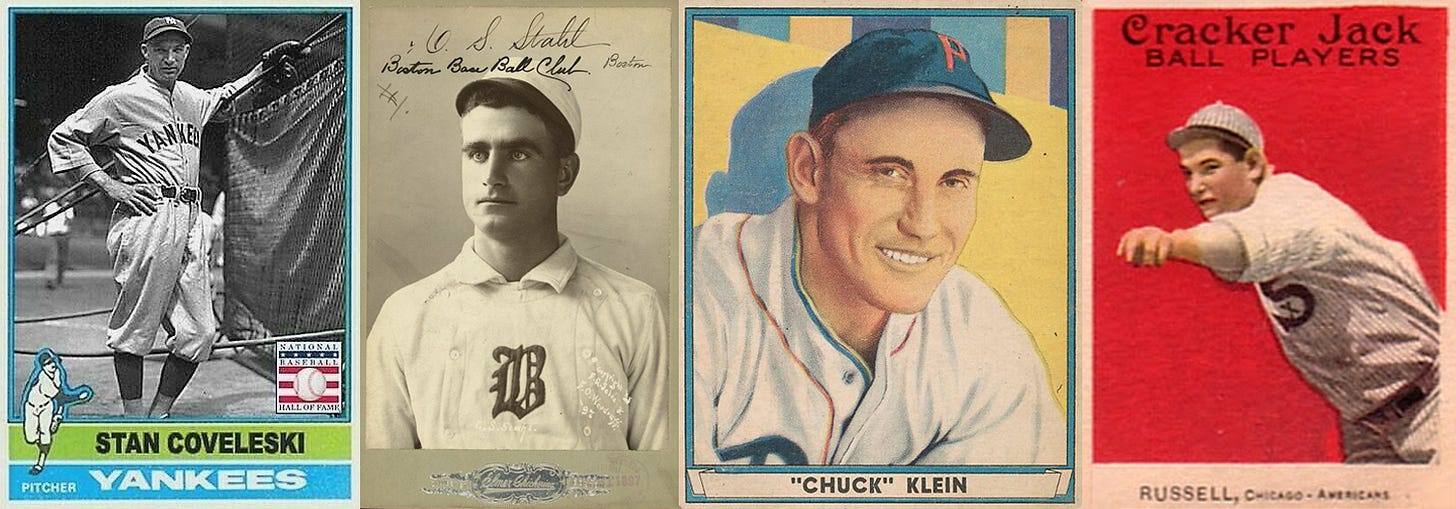

Just 2 miles from the minor league Cubs’ Four Winds Field lies Hall of Famer Stan Coveleski (62 WAR, St. Joseph Cemetery, South Bend). Coveleski was one of the foremost purveyors of the legal spitball in his era (1916-1928). The pitch was banned after 1920, but Coveleski was one of 17 pitchers grandfathered to continue throwing it. Or at least threatening to, as Coveleski would go to his mouth often, saying “I’d go maybe two or three innings without throwing a spitter, but I always had them looking for it.” Along with teammate (and aforementioned Alabamian) Joe Sewell, Coveleski’s Cleveland team won the 1920 World Series behind his three complete games (and 0.67 ERA), including a shutout in game seven.

Next we drive about 90 miles East-South-East for a Fort Wayne TinCaps (High-A, Padres) game. The team nickname is a Johnny Appleseed reference. “Paws and Claws” night is Wednesdays here, so plan accordingly.

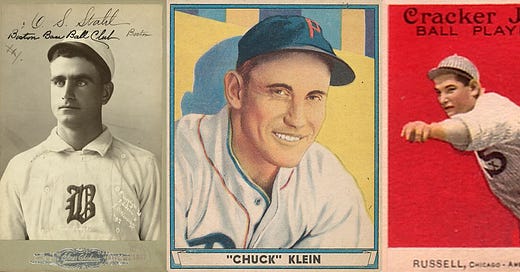

Our dead baseball player visitation here is Charles ”Chick” Stahl (31.6 WAR, Lindenwood Cemetery, Fort Wayne), who comes with a sad story, a mysterious death, and a suicide trigger warning. Stahl was one of baseball’s best hitters and outfielders from 1897 to 1906, playing for the Boston Beaneaters of the National League and the Boston Americans of the new American League. Described as a devout Catholic, popular among his teammates, but prone to depression, Stahl was seemingly on top of the world after the 1906 season. He had recently wed and was named player-manager of Boston, now called “The Chicks” after him. But on March 25, 1907, Stahl resigned as manager saying that the duties, especially releasing players, “make me sick at the heart.” Three days later, he was dead, poisoned by a self-administered dose of carbolic acid, which had been prescribed for a sore on his foot. Teammate Jimmy Collins saw Stahl fall back onto his bed and reported his last words were, “I couldn’t help it. I did it, Jim. It was killing me and I couldn’t stand it.” Allegations of infidelity appeared. One woman claimed to be carrying Stahl’s illegitimate child and threatened him with blackmail. Another report cited that “an intimate friend” of Stahl’s, one David Murphy of Fort Wayne, also committed suicide by swallowing carbolic acid, leaving a note that simply read, “Bury me beside Chick.” Was this the hidden relationship that drove the deeply religious Stahl to suicide? We’ll never know. Not without HBO’s Perry Mason we won’t!

I apologize. The emotional pain Stahl must have felt in those moments is tragic. Not all baseball stories are happy ones. Pour one out for Chick when in Fort Wayne.

Indianapolis is our next big city destination, with 64 buried players and the Indianapolis Indians (AAA, Pirates), the 2nd oldest continuously-operated minor league team (founded in 1902, behind only the Rochester Red Wings, 1899). There are no dog/White Claw promos that I can discern for 2024.

Just eleven minutes south of the Victory Stadium (“The Vic”) is where you’ll find Hall of Famer Chuck Klein (46.6 WAR, St. Joseph Cemetery, Indianapolis). He has one of the most impressive five-year runs of any ballplayer, anytime, anywhere. From 1929-1933, Klein hit .359, won four home run titles, an MVP, and a Triple Crown. His 44 outfield assists in 1930 is a modern-era record.

Cemetery-mate Ewell “Reb” Russell (28.1 WAR, St. Joseph Cemetery, Indianapolis) is not a Hall of Famer, but was a dominant pitcher for the 1913-1918 White Sox. Much like Gary’s Mostil, Russell injured his arm, luckily sitting out the 1919 “Black Sox” season, but returned as a right fielder to hit 22 home runs and post a 142 OPS+ in one and a half seasons for the Pirates. He is reportedly the inspiration for fictional character Jack Keefe, the overconfident rube in baseball journalist Ring Lardner’s novel You Know Me Al and the subsequent syndicated comic strip.

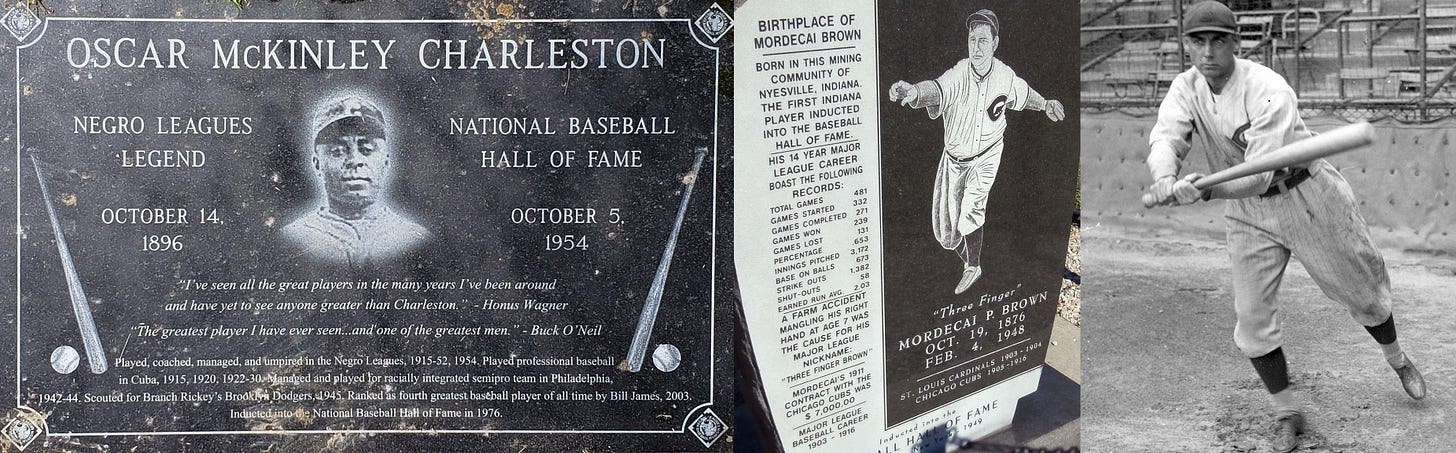

Indiana Hall of Famer #3 on our list is Oscar Charleston (48 WAR, Floral Park Cemetery, Indianapolis). As Negro League statistics are not as complete (but getting better all the time), we’ll go with these quotes from Charleston’s SABR bio to illustrate his incredible career.

A scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, Bennie Borgmann, once said, “In my opinion, the greatest ballplayer I’ve ever seen was Oscar Charleston. When I say this, I’m not overlooking Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, and all of them.”

Buck O’Neil said that Charleston “was like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Tris Speaker rolled into one.”

Honus Wagner said, “I’ve seen all the great players in the many years I’ve been around and have yet to see one any greater than Charleston.”

For more on Charleston, there is The Life and Legend of Baseball's Greatest Forgotten Player by Jeremy Beer.

Drive 90 minutes west to find Hall of Famer #4, Mordecai “Three Fingers” Brown (58.2 WAR, Roselawn Memorial Park, Terre Haute). To be accurate, Brown lost most of his right index finger to farming equipment as a child and broke his other fingers while chasing a rabbit, leaving a bent middle finger and paralyzed pinky. But Mordecai “Four and a Half Fingers” Brown doesn’t really roll off the tongue. The deformed hand enabled him to throw pitches not seen before. In the years that Brown pitched for the Cubs (1904-1912), the team went to four World Series, winning two championships. It didn’t hurt that Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance was the double play combo behind him.

Brown wrote a series of instruction manuals for kids in 1913, How to Pitch Curves. In the epilogue, he writes, “I would like to meet every one of you personally if such a thing were possible. But as it isn’t possible, I want you to believe right now that Mordecai Brown’s hand is reaching out to you in the distance and he is wishing you– good luck.” That’s so sweet. And terrifying. Three-Fingers completists will be compelled to also visit his birthplace memorial in Nyesville, 30 miles north of Terre Haute.

Ninety miles due south to Terre Haute we go. That is where we’ll find our fifth and final Indiana Hall of Famer, Edd Roush (45.8 WAR, Montgomery Cemetery, Oakland City). Roush was one of the Dead Ball Era’s premiere center fielders. His Cincinatti Reds beat the 1919 “Black Sox” in the World Series. At age 30, he led the league in doubles. At age 31, he led the league in triples. He won two National League batting titles in 1917 & 1919. But it’s Roush’s 1918 season that is singularly odd. He finished second in batting average (just two percentage points separated him from three straight batting titles), but led the league in slugging. Granted, ‘twas the Dead Ball Era; Babe Ruth led all of baseball with 11 home runs that year. But that weirdo Roush also led the league in… sacrifice bunts! Edd Roush, ladies and gentlemen, your slugging AND bunts leader of 1918. A feat that’s never been done by any other player in any season, not even close.

Last two Indiana stops, I swear. We’ll drive 23 miles east to Huntingburg, where League Field is home to the Dubois County Bombers of the Prospects League and… primary filming location for A League of Their Own (1992)! This was the Rockford Peaches stadium. While there is no Paws & Claws night, browsing the 2024 Bombers promo schedule is a riot (like "Let's Ridicule The Opposing Players with Humiliating Nicknames Night").

Final leg of the trip is 53 miles to the southernmost tip of Indiana, where the Evansville Otters play in the Frontier League. Again, there are no Paws/Claws specials, but the Otters’ home stadium, Bosse Field, served as the home of the Racine Belles in A League of Their Own!

That’s 10 hours of driving, but DAMN, Indiana, you’ve got it going on. Six teams in five different levels! We didn’t even fit in a visit to the Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame in Jasper (Hello, 2023 inductee Jeff Samardzija)!

But it’s the tales that go with the tombstones that stir the soul here at TTSS. Stories of the great ones. The weird ones. The lucky ones. The famous ones. The forgotten ones. The bad ones. And the sad ones. Every one of these players’ lives could be a TV movie of the week, an Unsolved Mysteries episode, a Serial-style podcast, or at least the b-story on a police procedural.

Where is the next great baseball story to hit the big screen coming from? Indiana, apparently.

Chuck Klein- wow in 154 games too. Just read that Phillies stadium had short RF fence so he'd play shallow and gun guys out at 1st on presumed singles!

Great column Jay! Walker bros. winning batting titles is a world class trivia question. Did a double take at "Indiana" as your subject.

Hoisting a beer to you "Fuzzy" Smith; you, sir are a great American.

Just Wed. wore my Memphis Chicks vintage-y tee. And wearing my Akron Rubber Ducks tee at the Asheville Tourists game last night, some guy yelled, "Rubber Ducks!" with a raised fist. It WAS $1 beer night after all (or Thirsty Thursday as they call it here).

That Negro League tribute game in B'Ham sounds like a perfect reason to visit.

Edd Roush slugging and bunt king another beauty of a trivia question.

Always a pleasure to read and appreciate the immense amount of work you put into TTSS.