We’re crossing into the heavy hitter states, commonwealths with more than a thousand total WARpC and hundreds of buried players. With the original impetus for this epic survey in mind, we’ll now focus on one cemetery per state. With just eleven states left to cover, we’ll soon arrive at the ultimate dead baseball player graveyard! Your stamina is appreciated.

First up today is Detroit, Michigan. From your casino hotel near Comerica Park, head north-west toward Southfield between ten-mile and eleven-mile to Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. It has the second most WARpC in the US! Two Hall of Famers headline, but the supporting cast ups the total to 285.7 WARpC.

Our first ballplayer is the thematic mascot for today’s post: Charlie “The Mechanical Man” Gehringer (83.8 WAR). He gets his nickname from the phrase “Wind him up in the spring and he goes all summer.” A second baseman from Livingston County, Michigan, Gehringer played his entire nineteen-year career with the Tigers (1924-1942), entrenching himself onto the all-time leaderboards. While Ty Cobb and Al Kaline take most of the top spots, Gehringer is in Detroit’s top four in hits, doubles, triples, total bases, RBI, runs, walks, and position player WAR. Wow. From age 24-37, he slashed .329/.411/.497, set a still-standing 511 games-played streak, and led Detroit to three World Series (winning in 1935 over the Cubs). And oh-by-the-way, he is second in assists all-time among all second baseman. The Mechanical Man was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1949, served on the veteran’s committee, and was on the board of directors until 1991.

Another Tigers legend rests here, Harry “The Horse” Heilmann (72.1 WAR). From 1916 to 1929, Heilmann was locked in as Detroit’s right fielder, accumulating four batting titles (including .403 in 1923), a career .342 batting average, and a 148 OPS+. He spent another seventeen years broadcasting Tigers games on radio. Heilmann died young, lung cancer at age 56 in 1951. He was elected to the Hall of Fame the next year.

Shortstop Billy “The Fire Chief” Rogell (24.8 WAR) also resides here. Along with Hank Greenberg at first, Gehringer at second, and Marv Owen at third, Rogell was the cornerstone of a quartet known as “The Battalion of Death”. Aptly named as they collected 466 RBI between them in 1934, their first season together. Rogell led the league in fielding percentage three straight years during the battalion’s reign. After his playing days, Rogell served as a Detroit city councilman for forty years. That’s why the Detroit Metro Airport (DTW) entrance is Rogell Drive. In September of 1999, he threw out the first pitch at the last game played at Tiger Stadium, almost seventy years after his debut there. He died of pneumonia in 2003 at 98 years old. Detroit loves a workhorse.

Next we’ll visit Hamtramck native Steve Gromek (25.1 WAR). He pitched seventeen seasons for Cleveland and Detroit (to a 3.41 ERA) and, according to his baseball card, pitched an 18-inning scoreless minor league game in 1943 that ended in a tie due to darkness. Gromek is maybe most remembered for a World Series photo. It wasn’t that Gromek had just pitched a complete game to put Cleveland up 3-1, or that his picture-mate Larry Doby had hit the game-winning home run, it was that a white ballplayer and a black one were celebrating cheek-to-cheek, arms around each other.

It was 1948. Integration of baseball was only in its second year. Doby was one of only seven black players in MLB. This feels simultaneously forever ago and not that long ago. How’s this for context: The Cleveland Indians were about to win that 1948 World Series, the last time that’s happened. Cleveland’s 77-year championship drought is the second longest in sports (behind the NFL’s Cardinals). Gromek was a good pitcher in the shadow of great ones and never get much credit. He was inducted into the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame in Troy, Michigan, in 1981.

Another Detroit local is up next, center fielder Barney McCosky (21.2 WAR). “Who?” you might be asking. McCosky can blame fascism for the anonymity. In his first four years with the Tigers, he slashed .316/.389/.440 for a 112 OPS+. But McCosky’s career was interrupted by three years of World War II service in the Navy. He returned to have some good, if nondescript, years with Philadelphia, Cincinnati and Cleveland. He is memorialized in the Dave Frishberg song “Van Lingle Mungo” right between Big Johnny Mize and Hal Trosky.

I know this is getting extensive, but that’s what we do here. We’ll wrap up Michigan and Holy Sepulchre Cemetery with two more Detroit natives with lengthy careers, Dick “The Monster” Radatz (15.6 WAR) and Harry “Nemo” Leibold (10.6 WAR). Radatz was 6’6”, 230 pounds, and dominated as a reliever for the first three years of his career with the Red Sox (181 ERA+ over 414 innings from 1962-1964), then flamed out (81 ERA+ over his next four years). He is in the Red Sox Hall of Fame. Leibold was a speedy outfielder who traversed the deadball-to-liveball eras (1913-1925), and, at 5’ 6”, was named after a popular comic strip “Little Nemo.” Despite being a member of the 1919 Black Sox World Series team, he escaped contamination to play another five seasons, including winning a World Series with the 1925 Washington Senators. Leibold went on to manage minor league teams for twenty-one years. That’s the long and short of it for Michigan!

To Baltimore, Maryland we go. Charm City wallops most other municipalities with 522.8 city-wide WARpC. Our single cemetery destination, New Cathedral Cemetery (229 WARpC, fifth among all cemeteries), features a WAR leader who is not in the Hall of Fame, three Hall of Fame managers, and a knuckleballer-turned-umpire. And it’s just five miles west of Camden Yards.

Pitcher Bobby Mathews’ (55.1 WAR) career stat line illustrates the limitations of statistical valuation. Mathews is credited with the win in the first-ever professional league game. He pitched more than 400 innings in a season seven times. In 1875 alone, he pitched 69 complete games and 625.2 innings! His incredible career (1871-1887) mandates a graveside visit, but comparing him to modern-era players is brain-melting at best, hence no Hall of Fame for Mr. Mathews. Nonetheless, SABR designated him their Overlooked 19th Century Legend in 2023. In that same year, SABR gave him a new grave marker 120 years after his death at age forty-six (most-commonly attributed to syphilis). Different times, indeed.

On a lighter note, catcher Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson (6.7 WAR) played seventeen years, but is in the Hall of Fame as a manager (including 18 years leading the Brooklyn Robins/Dodgers). That’s not a career, that’s a life in baseball from 1886 to 1931. At the time of his death, he was the President of the minor league Atlanta Crackers. The New York Times said, “His conversation was a continuous flow of homely philosophy, baseball lore, and good humor. He knew baseball as the spotted setter knows the secrets of quail hunting, by instinct and experience.”

Please, please, please compare me to a hunting dog after I’m dead.

Our second Hall of Fame Manager— the one with ten pennants, three World Series championships, and second in all-time wins— is baseball luminary John McGraw. He is interred in a mausoleum not far from Robinson, his teammate and long-time friend/rival. Sorry Mugsy, the more famous you are, the less words we spew forth here at TTSS.

Hall of Fame manager three is “Foxy Ned” Hanlon. In his nineteen years of managing (1889-1907), he is credited with the following innovations: the hit-and-run, the squeeze play, signs, the delayed steal, platooning, a pitching rotation, spring training, and the infield fly rule. He managed cemetery-mates Robinson and McGraw (and Hall of Famer Connie Mack) in their playing days. He is maybe the most deserving of the many known as “The Father of Modern Baseball.” Also, please, please, please refer to me as “Foxy Jay” after I’m dead.

Our next Hall of Famer gravesite at New Cathedral is speedy outfielder Joe “Kingpin of the Orioles” Kelley (50.5 WAR), a teammate of McGraw, Robinson, and Hanlon. Kelley is 52nd in all-time on-base percentage (.402), and 56th in stolen bases (443). Weirdly impressive, but he’s not this Joe Kelly.

For our last stop at New Cathedral Cemetery, we visit Eddie Rommel (49.8 WAR), Philadelphia Athletics pitcher (1920-1932), “Father of the Modern Knuckleball,” and American League umpire! Rommel’s up-and-down playing career illustrates the least telling of all baseball statistics: Pitcher Wins. His 23 loses in 1921 were the most in baseball. He then led the league in wins the next year with 27 and finished 2nd in MVP voting. His ERA+ was 113 in the losing year (13% better than league average) and 129 in the wining year. The real telling stat, and maybe the only stat that actually matters: his team lost 100 and 89 games in those two years.

Those Athletics, led by manager Connie Mack with Rommel as his workhorse (a league-leading 501 appearances over his career), would persevere and prosper, winning the World Series in 1929 and 1930.

After retiring from his playing days, it was Connie Mack’s suggestion that Rommel consider a second career in baseball. After 3 years umpiring in the minors, Rommel was promoted to the American League and stayed for 22 years (1938-1959). He umpired six All-Star Games and two World Series. In 1956, he was the first-ever umpire to wear eyeglasses in a game. Rommel lived the last 47 years of his life in a row house in Baltimore, owned a duckpin bowling alley, and said this of his second career, “You’re a bum when you walk out there on the field and you’ll be a bum when you walk off it… You can’t please everybody.”

All told there are thirteen Hall of Famers permanently residing throughout Maryland, including two of the best pitcher of all time, Walter Johnson (167.8 WAR Rockville Cemetery, Rockville) and Lefty Grove (106.8 WAR, Frostburg Memorial Park, Frostburg).

Johnson led the league in strikeouts in 12 of his 20 seasons (1907-1927) and holds the never-to-be-broken record of 110 career complete-game shutouts. For context, the shutout leader among active pitchers is Clayton Kershaw with fifteen. There are 394 pitchers on the list ahead of him. We are unfairly comparing two human beings who did their best work 98 years apart. Baseball has changed dramatically in that time and also not at all.

In one of the most famous pitching duels of all time, Johnson faced the aforementioned Rommel on opening day 1926. The two pitchers matched zeros for 15 innings. Johnson’s Washington Senators eventually won 1-0.

Lefty Grove accumulated gaudy numbers over his career with the Athletics (1925-1933) and Red Sox (1934-1941): nine ERA titles, led the league in strikeouts seven times, six All-Star Games (the game didn’t exist until he was 33 years old), and an MVP Award. In eight World Series games (51 innings), Grove had a 1.75 ERA, with 36 strikeouts and 6 walks. He was a member of those WS winning Athletics with Rommel in 1929 and 1930.

The through line of today’s post is longevity. Is that the key to success and (Halls of) fame? The game itself has endured. The commonly acknowledged first professional baseball contest (the game won by Bobby Matthews) was in 1871, ONE HUNDRED FIFTY-FOUR years prior to this writing. For baseball players, durability and perseverance are requisite factors to reaching the profession’s highest honor, enshrinement into the Baseball Hall of Fame. “Compilers.” That is how these long-career players are often referred to.

Everything is measured in baseball, now more than ever. Is it reductive? Absolutely. A statistic (say… a player’s career hits total, just to pick one at random) doesn’t elucidate a player’s character. OPS+ can’t tell you if they broke the most basic rule of the game. CWPA won’t tell you if they were actually an unrepentant asshole. It’s Pete Rose. I’m making fun of Pete Rose.

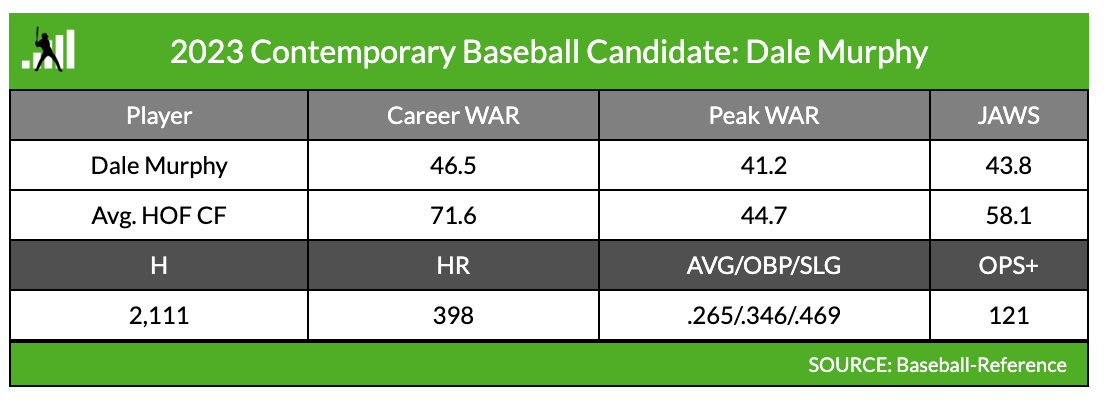

But numbers will tell you if your baseball career is Hall of Fame worthy. Baseball writer and researcher Jay Jaffe has created a metric for this, Jaffe Wins Above Replacement Score (JAWS). It allows for prospective inductees to be compared to the consortium of enshrined players at each position. The metric averages career WAR with the WAR accumulated during a player’s 7-year heyday, balancing longevity and peak performance.

The office of TTSS holds a few truths to be self-evident. One of them is that Hall of Fame discourse is resoundingly tedious. Adding math turns the wide varieties of opinion into more of a yes/no proposition. Let’s take a quick look at two Hall of Fame cases, outfielders Dale Murphy and Andruw Jones.

As much as these player are equally beloved, the numbers differentiate them. Dale Murphy goes in the Hall of VERY GOOD and VERY NICE, but doesn’t ascend to the actual Hall of Fame, numbers-wise.

For Andruw Jones, let’s quote the man himself.

Over the past five [HoF voting] cycles, Jones has jumped to 19.4%, 33.9%, 41.4%, 58.1%, and 61.6%, to a point where eventual election, either by the writers or a small committee, has become not just a possibility but a likelihood. With three years of eligibility remaining, he still has a very good chance to get to 75% from the writers.

-Jay Jaffe

The Jaffe quote alludes to the convoluted election system for the Hall of Fame. That’s another sticky morass that we’ll avoid today. We’re NOT going to talk about Harold Baines.

Numbers. Crisp and precise. There is something comforting about being measured so completely. It’s concrete. There are no competing points of view. The numbers don’t take sides. They tell the story in their own way. Baseball player success, or failure, is always in the numbers.

We non-professional athletes have to measure our careers by other means. I’m a TV/Film editor when not watching/writing/thinking about baseball. No one can quantify if I’m the most efficient, the most creative, the most bartender-meets-therapist-meets-engineer indie film editor in the world. I think I am, but there’s no metric for that. Baseball players are lucky. They leave the quantifying to someone else. The rest of us have to construct our own self-confidence Hall of Fame from scratch.

Longevity counts here too. I’ll keep editing. And writing about baseball. So if you’re reading this in the 2030s or 2040s or 2050s, it worked. Please tell a friend, “Foxy Jay Wade… He was the Brussels Griffon of baseball writers… The Labradoodle of film editors… wind him up and he edits all night…”

I love being introduced to random awesome players I might not have otherwise, like Bobby Mathews (and Steve Gromek), so thanks for that!

PS: For me, personally, Andruw Jones, should be a HoF lock.

Jay your research is fascinating as always.

Never knew Walter Johnson was buried in Rockville, 5-6 blocks from the street intersection site of our childhood stickball and football games. Unfortunately we didn't have corn fields. "Car, car, C-A-R!"

Bobby Mathews' numbers are incredible- he was pitching underhand until 1884 so a little easier on the arm. Overhand pitching must've killed his career like talkies did to silent movie stars.

Other oddities: back in the 1860's-'70's the umpires would often sit in a chair behind the pitcher's mound, the batter would dictate to the pitcher where he wanted the pitch (pitch was called a ball if the pitcher missed), fielders could hit a runner with a thrown ball for an out (kickball!), and a catch on one bounce was also an out- without gloves this was a fair accomplishment.

As fans we tend to take modern baseball rules as obvious (except for Sam Holbrook who couldn't comprehend the spirit of the infield fly rule 2012 Braves v Cards), but they slowly evolved year by year, idea by idea and trial and error as does every human endeavor.